For the last couple of months, I have been working on building a command and control framework using the Nim programming language called Conquest. While the development of the tool is still actively ongoing, I am pretty happy with the design of the C2 communication between the team server and the framework’s agents. This blog post outlines how I am combining symmetric and asymmetric cryptography to secure C2 traffic, ensuring that both the confidentiality and integrity of the network packets are guaranteed.

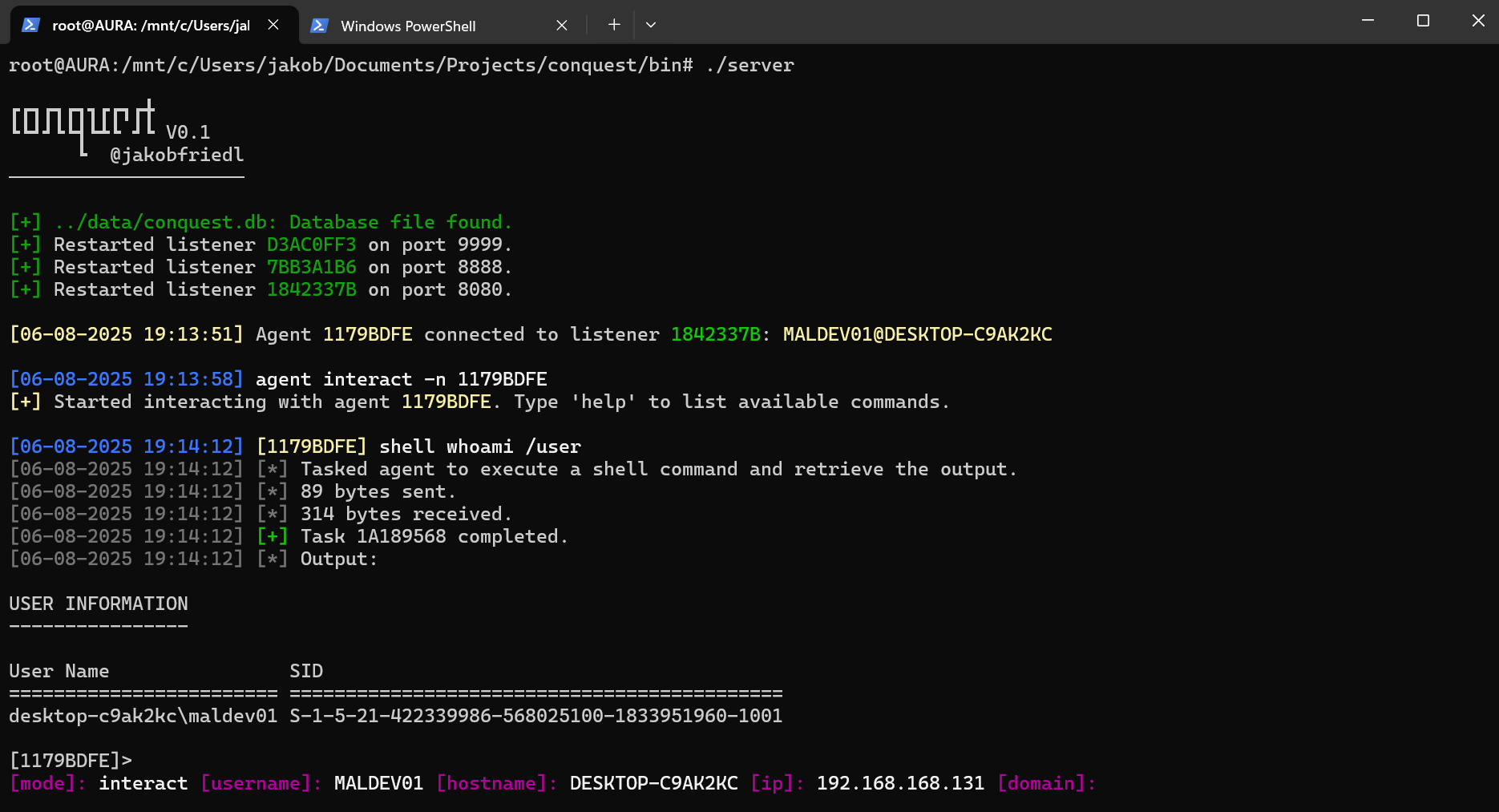

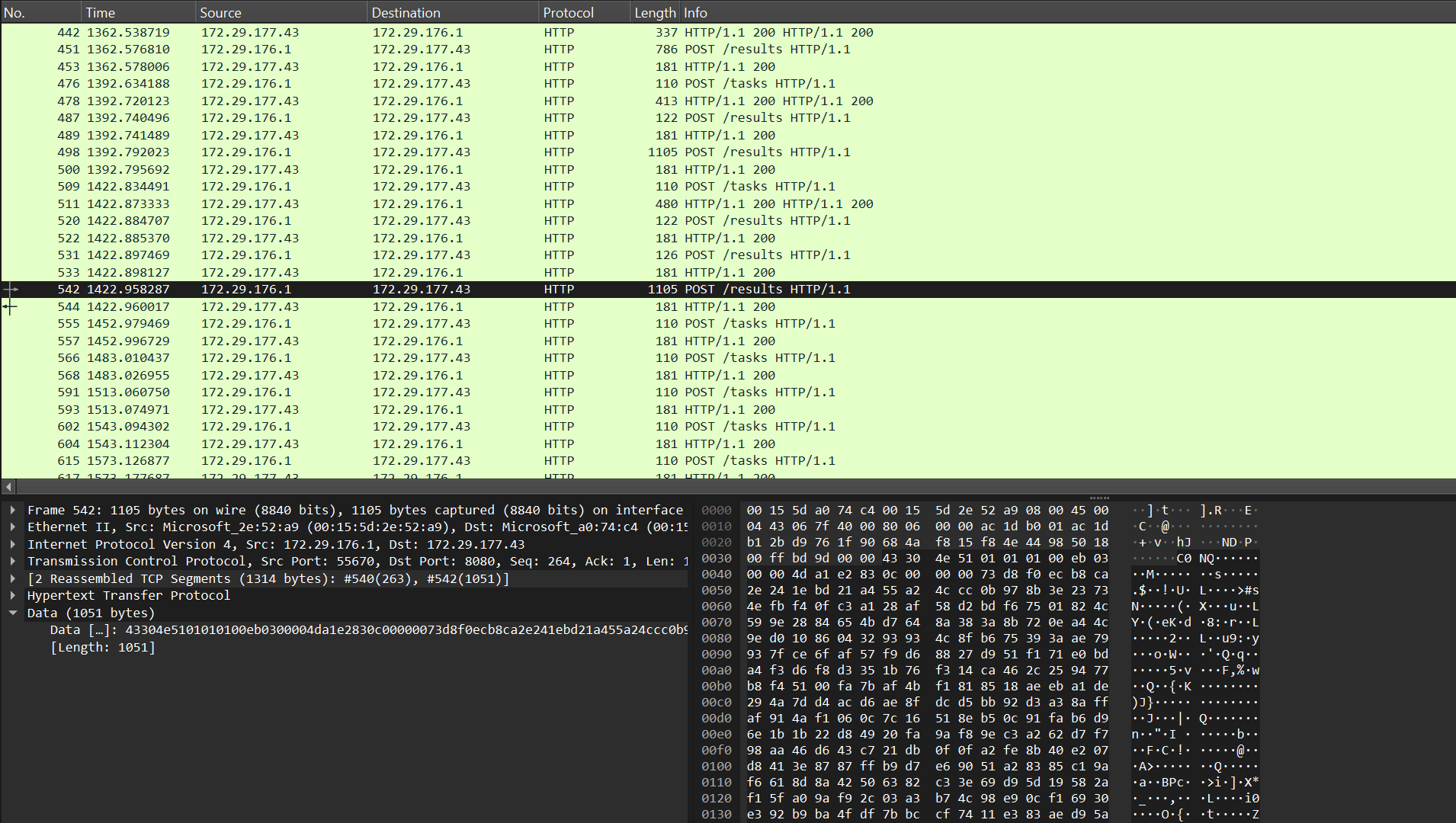

Similar to many other C2 frameworks, Conquest consists of a team server, which currently functions as the main user interface, and an agent, which periodically checks in to a listener to poll for new tasks or to post the results of a completed task, such as the output of a console command. The communication between agent and server occurs over HTTP, with the agent sending HTTP POST requests to specific endpoints on the listener. The major problem with HTTP traffic is that any data included in the request is sent in cleartext, which is catastrophic for a tool designed to extract and exfiltrate sensitive data, such as system information, files or credentials from a target system. It is imperative to implement strong encryption, which ensures that only authorized parties can decrypt and read the contents of the network packets.

Packet Structure

Conquest’s C2 communication uses 4 distinct types of packets:

- Registration: The first message that a new agent sends to the team server to register itself to it. Contains metadata to identify the agent and the system it is running on, such as the IP-address, hostname and current username.

- Heartbeat: Small check-in requests that tell the team server that the agent is still alive and waiting for tasks.

- Task: When an operator interacts with an agents and executes a command, a task packet is dispatched that contains the command to be executed and all arguments.

- Result: After an agent completes a task, it sends a packet containing the command output to the team server, which displays the result to the operator.

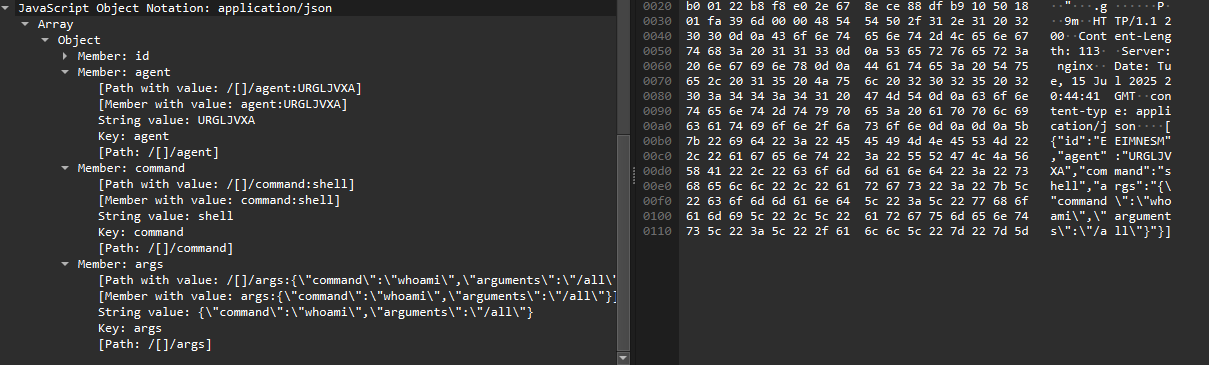

Originally, I chose the JSON format for the network communication, due to it being easy to implement and simple to parse. However, I soon realized that I would need a more flexible approach to support optional and differently typed arguments, as well as to implement features such as payload encryption properly. As seen in the Wireshark screenshot below, strings in JSON are clearly visible, allowing analysts to effortlessly classify the network traffic as C2 communication. Encrypting sensitive contents would lead to large base64-encoded strings being transmitted, which would look extremely suspicious as well.

Header

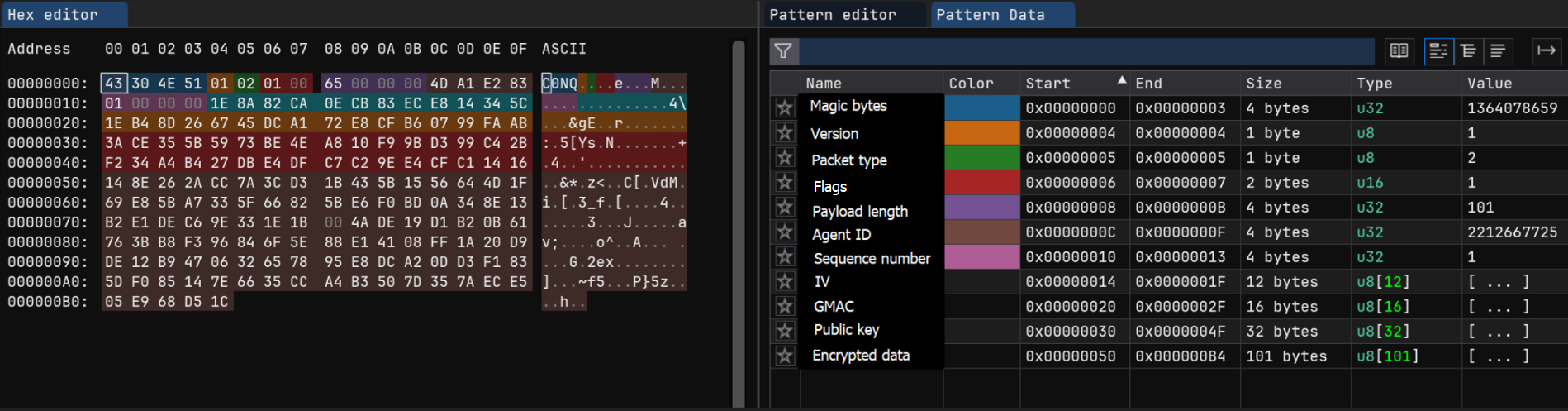

To address these limitations, I decided to ditch the JSON approach and focused on essentially designing a binary protocol from scratch instead. Each packet consists of a fixed-size header and a variable-length body, with the header containing important unencrypted metadata that helps the recipient process the rest of the packet. Among other fields, it contains the 4-byte hex-identifier of the agent, which tells the team server which agent is polling for tasks or posting results. The variable-length payload body is encrypted using AES-256 GCM using a asymmetrically shared session key and a randomly generated initialization vector (IV), which is included in the header for every message. The GCM mode of operation creates the 16-byte Galois Message Authentication Code (GMAC), which is used to verify that the message has not been tampered with. The cryptographic implementations are more thoroughly explained in sections Key Exchange and Packet Encryption

0 1 2 3 4

├───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┤

4 │ Magic Value │

├───────────────┬───────────────┬───────────────────────────────┤

8 │ Version │ Packet Type │ Packet Flags │

├───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────────────────────┤

12 │ Payload Size │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

16 │ Agent ID │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

20 │ Sequence Number │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

24 │ │

28 │ IV (12 bytes) │

32 │ │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

36 │ │

40 │ GMAC Authentication Tag │

44 │ (16 bytes) │

48 │ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

[Header]

Task Packet

While the structure of the header stays the same across all packet types, it is the encrypted payload body that changes. When a new task is dispatched and fetched by an agent, a packet with the structure below is created. It contains the ID of the task, listener and command to be executed, as well as a list of arguments that have been passed to the command.

0 2 4 6 8

├───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┤

0 │ |

| Header (48 bytes) |

| |

├───────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────┤

48 │ Task ID │ Listener ID │

├───────────────────────────────┼───────────────┬────────┬──────┤

56 | Timestamp │ CMD │ ARGC │ │

├───────────────────────────────┴───────────────┴────────┘ │

│ │

│ Argument 1 │

│ │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Argument X │

│ ... │

?? │ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

[Task]

The number of arguments the agent needs to process is indicated by the argument count (argc) field. The first byte of an argument defines the argument’s type, such as INT, STRING or BINARY. While some argument types have fixed sized (boolean = 1 byte, integers = 4 bytes, …), variable-length arguments, such as strings or binary data are further prefixed with a 4-byte data length field that tells the recipient how many bytes they have to read until the next argument is defined. For example, the command shell whoami /all would produce the following packet body, before it would be encrypted.

DE AD BE EF DE AD BE EF 12 34 56 78 01 00 02 00 06 00 00 00 77 68 6F 61 6D 69 00 04 00 00 00 2F 61 6C 6C

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └─┬─┘ └┤ └┤ └────┬────┘ └───────┬───────┘ └┤ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

Task Listener Timestamp │ │ │ Length: 6 'whoami' │ Length: 4 '/all'

│ │ │ │

Command ID: 'shell' │ Arg Type: String Arg Type: String

│

Arg Count: 2

Result Packet

For each task that an agent executes, a result packet is sent to the team server. This packet is structured similarly to the task, with the difference being that it contains the task output instead of the arguments. The Status field indicates whether the task was completed successfully or if an error was encountered during the execution. The Type field informs the team server of the data type of the task output, with the options being STRING, BINARY or NO_OUTPUT. While string data would be displayed in the user interface to the operator, binary data could be written directly to a file.

0 2 4 6 8

├───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┤

0 │ |

| Header (48 bytes) |

| |

├───────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────┤

48 │ Task ID │ Listener ID │

├───────────────────────────────┼───────────────┬────────┬──────┤

56 | Timestamp │ CMD │ Status │ Type │

├───────────────────────────────┼───────────────┴────────┴──────┤

64 │ Length │ │

├───────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Result Data │

?? │ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

[Result]

As far as the payload bodies of the other message types are concerned, the heartbeat message only contains the listener ID and a timestamp, while the registration payload includes information collected from the host the agent is running on, including username, hostname, IPv4 address, information about the operating system and information about the process the agent is running in. As with the command arguments, variable-length data fields contain a 4-byte prefix which defines the length of the data that follows. Alongside this metadata, the agent registration packet also contains the public key of the agent, which is then used by the team server to derive the AES encryption key, as outlined in the subsequent section in more detail.

Key Exchange

As mentioned before, the payload body of a network packet is serialized and encrypted. With symmetric ciphers like AES, the agent and team server have to agree on the same encryption key to process the data. However, the key exchange is far more difficult than just sending a randomly generated key over the network, as this would allow anyone to intercept and use it to decrypt and read the C2 traffic. The solution to this dilemma is public key cryptography. The server and all agents own a key pair, consisting of a private key that is kept secret and a public key which can be shared with everyone. The approach I originally considered was to use RSA1, where the agent generates an AES session key, encrypts it with the server’s public key and then embeds the encrypted key into the registration packet. However, due to the large key size required and computational overhead, I opted to go with the more elegant X255192 key exchange, which is based on elliptic-curve cryptography3. On a high level, it involves the following steps:

- Both parties generate a 32-byte private key, from which they derive the corresponding public key.

- Both parties calculate a shared secret by using their own private key and the other’s public key.

- A 32-byte session key is derived from the shared secret, which is used to encrypt all C2 communication.

- Ephemeral keys, such as the agent’s private key and the shared secret are wiped from memory as soon as they are no longer needed to prevent them from being compromised.

While the Nim language does not offer many battle-tested ECC libraries, it has some useful language features that made the implementation of the key exchange straightforward and elegant. Due to Nim’s excellent interoperability with the C language via its foreign function interface (FFI), I was able to create a wrapper for the Monocypher crypto-library to use it’s X25519 implementation.

Using the {.compile.} directive, the Monocypher library is directly included in the Nim build process, allowing the import of functions defined in the C source code using the {.importc.} pragma shown below.

| |

Although it is possible to use the imported functions with their C types, it is preferred to implement wrapper functions that use Nim types instead, as shown using the keyExchange function below for example. This highly increases the comprehensibility of the code and makes it easier to use.

| |

As mentioned before, the key exchange calculates a shared secret that is used for key derivation. This secret is, however, not suitable to be used as the encryption key, as it is not cryptographically random. To derive a session key, the secret is hashed using the Blake2B hashing algorithm along with some other information, such as the public keys and a message, to create a secure 32-byte key.

| |

With the actual key derivation covered, one question remains: How do the agent and the team server exchange their public keys? As the agent initiates the C2 communication, I needs to have the server’s public key embedded into it’s binary to avoid unnecessary network handshakes. This is straightforward to implement, thanks to Nim’s compile-time variables. By adding the -d flag to the Nim compiler, we can pass values to variables that are defined using the {.strdefine.} or {.intdefine.} pragmas, making this feature incredibly useful for adding listener configuration to the agent or embedding the server’s public key.

| |

In addition to processing compiler flags passed to the command-line, Nim also checks for configuration files named nim.cfg or config.nims in the current directory. I implemented an agent build process into Conquest, where this configuration file is overwritten with the relevant information, such as the IP address and port of the listener or the standard sleep delay. For the above-mentioned compile-time define pragmas, a nim.cfg file could look like the following.

| |

When the agent is executed, it generates its own key pair. Using the newly created private key and the servers’ public key, it subsequently derives the session key used for the packet encryption. At that point, the agent can wipe its own private key from memory, as it is no longer needed. For the server to be able to derive the same session key, the agent includes its public key in the registration packet.

0 4 8 12 16

├───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┴───────────────┤

0 │ |

| Header (48 bytes) |

| |

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

48 │ Agent Public Key │

│ (32 bytes) │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

80 │ │

│ │

│ Encrypted Metadata │

│ │

│ │

?? │ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

[Registration]

When the server deserializes and parses the registration packet, it uses its own private key and the agent’s public key to derive the same session key and stores it in a database. Following this exchange, all communication between an agent and the server is encrypted using this session key as explained in the following section.

Packet Encryption

With the key exchange completed, what follows is the encryption of a network packet’s body using the AES-256 block cipher in the Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) mode of operation45. GCM provides authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD), ensuring that both confidentiality and integrity are guaranteed. This is achieved by combining the Counter Mode (CTR) for encryption and GHASH for authentication. In addition to encrypting the data, an authentication tag, also known as Galois Message Authentication Code (GMAC) is calculated based on the encrypted data and additional authenticated data (AAD). AAD is any unencrypted data, for which integrity and authenticity should be ensured, such as the sequence number that prevents packet replay attacks. If the ciphertext or sequence number of a packet are modified before it is received, the recipient’s recalculation of the 16-byte GMAC will not match the tag included in the packet header, allowing the server or agent to detect tampering and discard the packet.

The nimcrypto library provides a easy-to-use AES-GCM implementation in Nim. As mentioned before, the packet’s sequence number is added as AAD to ensure that modifications made to it are detected.

| |

Looking at a registration request in Wireshark, we can see and differentiate the fields in the packet. The registration packet kicks off the sequence tracking with the sequence number 1, which is then incremented for each task and result packet sent. This sequence number is validated whenever a packet is received to prevent replay attacks. The hex data below also clearly shows the 12-byte IV, 16-byte GMAC and 32-byte public key. The byte-array with 101 entries contains the encrypted metadata collected from the target host.

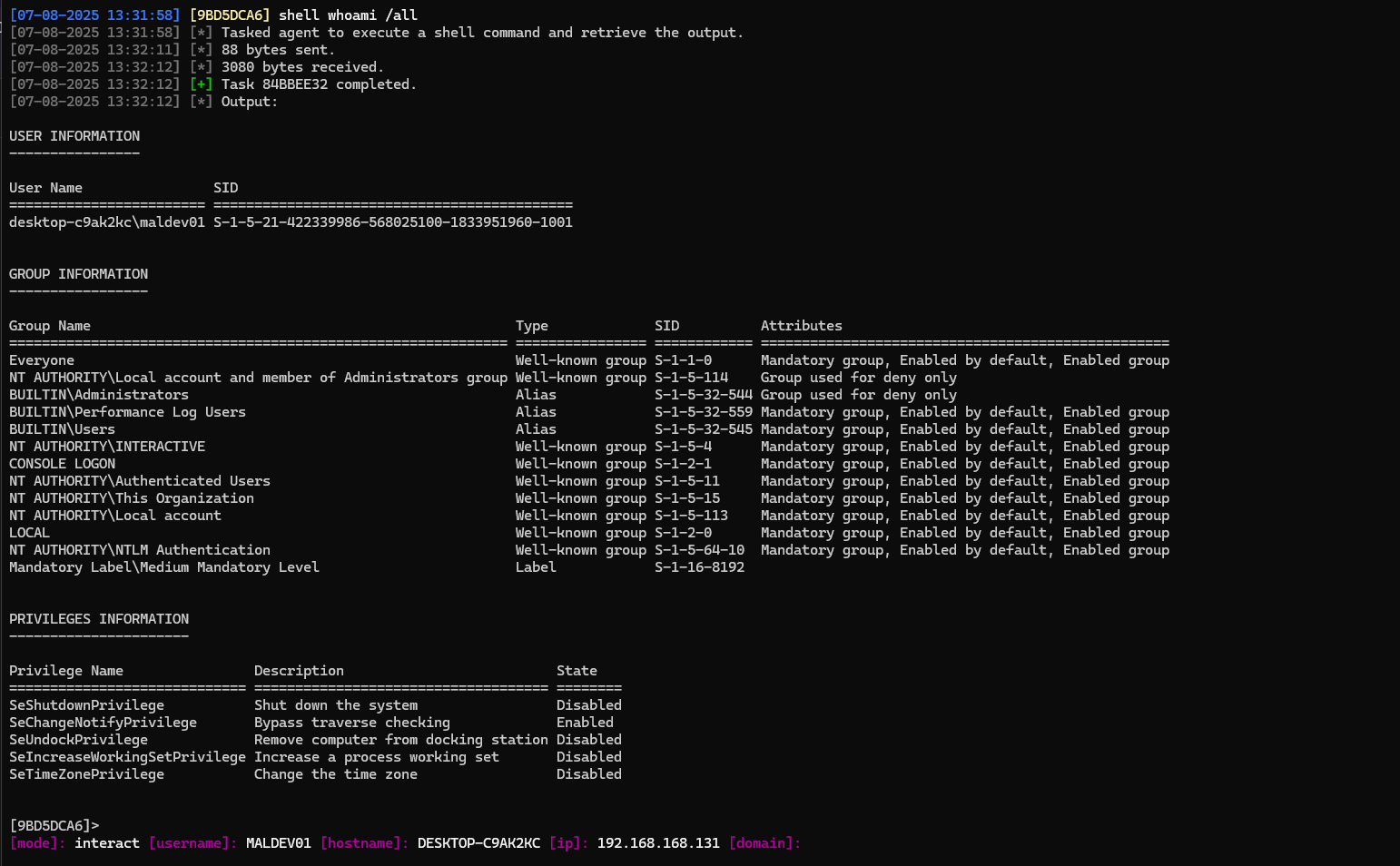

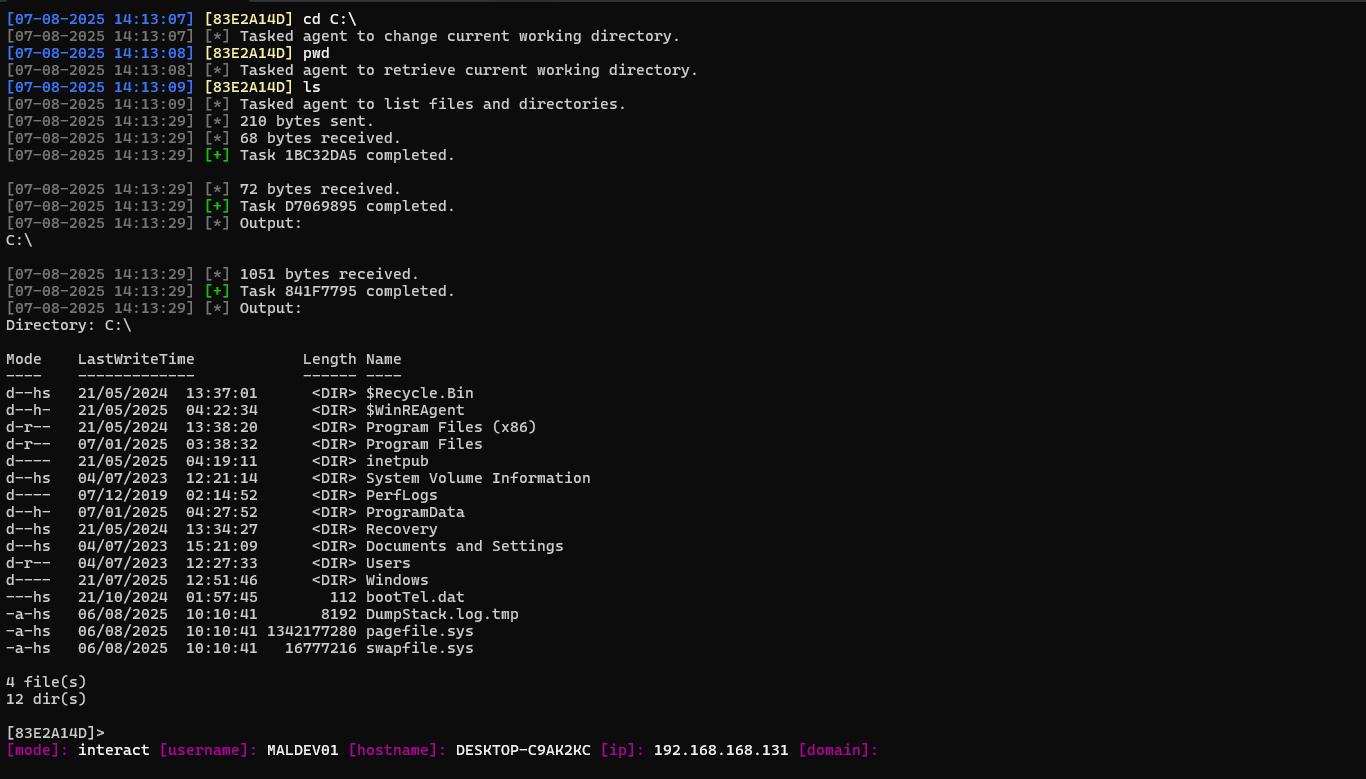

Demo

This section’s purpose is to showcase the C2 traffic generated by the Conquest framework, parts of the user interface and some of the implemented commands and modules.

Closing Remarks

Even though I find myself constantly rewriting parts of Conquest, such as the module system or serialization logic, I feel that the cryptographic aspect of the C2 traffic is pretty well designed and doesn’t require too many improvements for now. Finishing the CRTO course and getting to know my way around Cobalt Strike, has sparked many more ideas I want to implement in my own framework, such as a functional token impersonation system. This project is currently closed-source, as I want to work on it privately until I feel like it’s established enough to deserve a proper release. This will, however, not stop me from documenting my development journey with blog posts when I’m hitting milestones on certain technical implementations.

https://www.onlinehashcrack.com/guides/cryptography-algorithms/x25519-key-exchange-fast-secure-guide.php ↩︎

Elliptic-curve cryptography (Computerphile): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NF1pwjL9-DE ↩︎

AES GCM (Computerphile): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fpVv_T4xwA ↩︎